This post explores natural langugage processing models for applied NLP. In particular, it digs into a particular model for Semantic Role Labeling, discussing some ways in which I think it can be applied in practice. After that, it goes off on a bit of a tangent, with some exploration of what we should care about within SRL as a formalism and some very crude ways to fix them, resulting in a nice improvement to an existing SRL model.

Some of the ideas in this post point to a relatively bold hypothesis - that the applied natural language processing community has accidentally drifted into producing models for syntax, because they are popular in academia, whereas in reality, they are not the best choice for creating effective natural language understanding applications.

Why Syntax?

Models for syntactic analysis have a lot going for them. Syntax is a large area of ongoing research; models built for syntax often operate over trees, which are efficient; and many open source libraries provide models in a wide variety of languages. The Universal Dependencies project is probably the largest annotation effort in NLP. It really has a lot going for it - it's open source and (broadly) very liberally licensed. It has a huge number of treebanks in many different domains for over 90 languages, and it's backed by rigorous linguistic theory that has stood the test of time.

Why not Syntax?

Using models for syntax in practice do raise some problems however. The most common one is the variation of syntactic constructions for the same event. For example, all of these statements have very different syntactic constructions:

Bill Gates is the cofounder of Microsoft

The cofounder of Microsoft, Bill gates, ...

Microsoft's cofounder, Bill Gates, said today ...

Bill Gates, the cofounder of Microsoft, said ...

Bill Gates, Microsoft cofounder, said today ...I hope that it is reasonable to say that most applied NLP tasks focus on semantic relations (e.g co-founder of) and so this syntactic variablity makes using syntax as a core building block hard to swallow.

Another less commonly discussed problem with dependency parsing is how they are evaluated. Labeled and Unlabeled Attachment Score measure the accuracy of attachement decisions in a dependency tree (with labeled additionally considering the label of the dependency arc). It has always struck me as quite bizzare why this evaluation is accepted in the research community, given the standards of evaluation in other common NLP tasks such as NER. Clearly, there is a precision vs recall tradeoff in the attachment decisions made by a dependency parsing model, but this is rarely reported. To find really good analysis on this point, we have to go back quite some way to Analyzing and Integrating Dependency Parsers by Ryan McDonald and Joakim Nivre.

Overall, I believe this metric causes an over-estimation of the performance of most dependency parsers for practitioners. For example, the Stack Pointer Parser from Ma and Hovy, 2018 achieves 96.12% UAS on the Penn Treebank - but when viewed at the sentence level (all dependencies completely correct), this corresponds to only 62% unlabeled accuracy (and 55% for LAS!). Obviously this drop in performance is expected, but this relates to a slightly more cogent point below, when we look at this gap relative to another task.

A Quick Foray into Applied NLP tasks

I am a big fan of Ines Montani/Matthew Honnibal's approach to thinking about practical NLP annotation, which you can listen to in this easily digestable video from Ines. Basically, the idea is that there are very few tasks which can't be broken down into text classification and/or Named Entity Recognition when used in a practical setting.

A good example of this is Relation Extraction, a very popualar task in industry. When thinking about an end user interface for relation extraction, you almost certainly want the relation in the context of a sentence a human can read anyway - so why not just do text classification? If we wanted to get fancy, we could also do Named Entity Recognition so a user could search for relation-containing sentences which contain particular entity types.

A wild task format appears!

Over the last few years, I have come across several examples of tasks which are slightly more complex than this combination of text classification and NER, which I am going to call Almost Semantic Role Labeling. This task can be broadly described as span prediction conditioned on a word or phrase in the sentence.

This naming will probably make lots of NLP researchers stamp their feet and tell me that I mean "close to arbitrary structured prediction", which is probably true - but we'll stick with Almost Semantic Role Labeling for the time being, given it's the most similar. It turns out that Almost Semantic Role Labeling is constrained in a particular way which makes it very easy to buid models for, which is important for practical use.

The underlying model

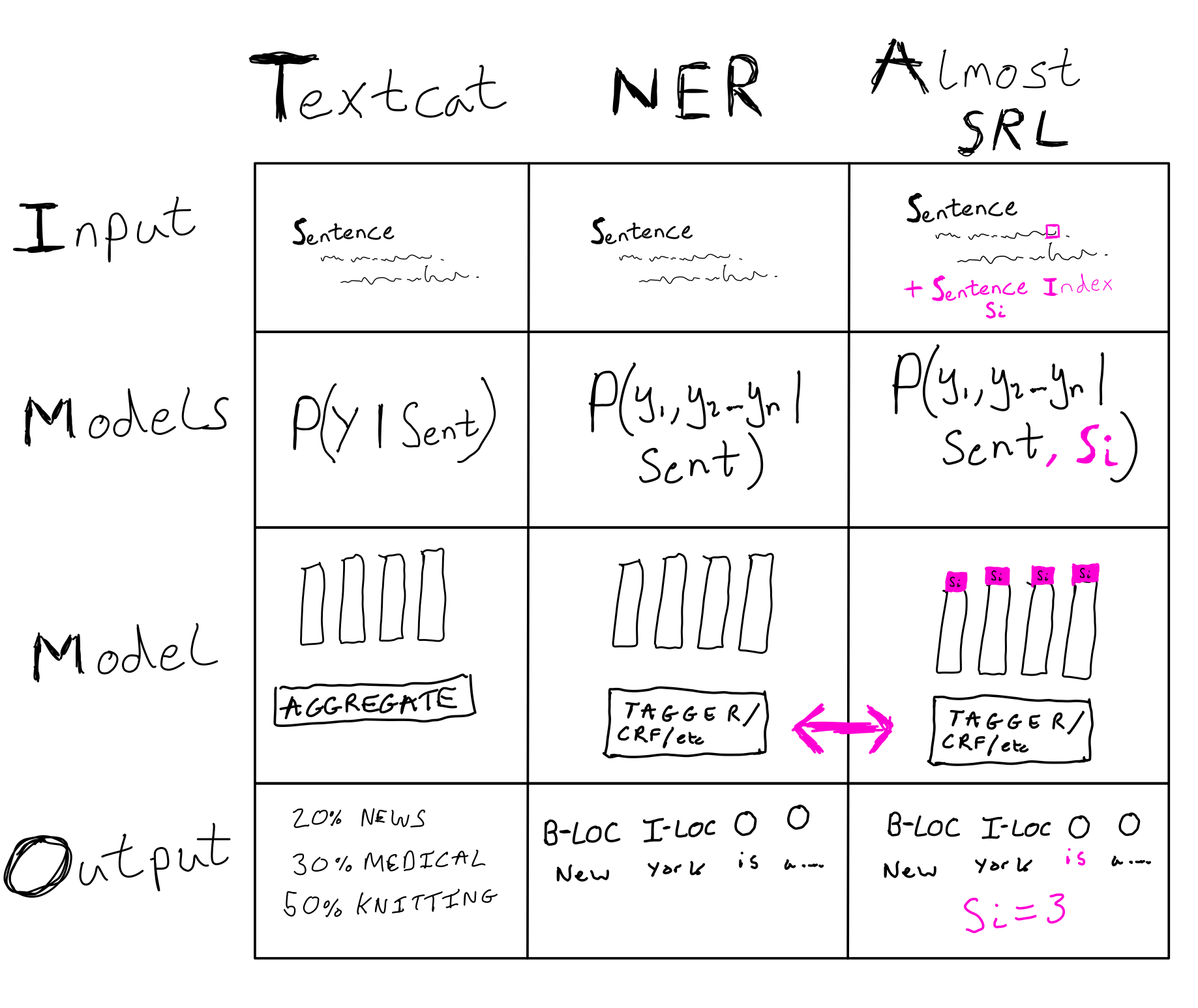

Why is viewing these types of structured prediction task in this way so useful? To think about this, it is helpful to consider the inputs and outputs of these classifiers:

- Text Classification: Input: (Text) -> Label/s

- Named Entity Recognition: Input: (Text) -> Labeled Spans

- Almost Semantic Role Labeling: (Text, text index) -> Labeled Spans

This small extension allows models which are much more expressive for zero modelling cost, due to a cute trick which allows us to view Almost Semantic Role Labeling in exactly the same way as NER. From a modelling perspective, doing something as simple as concatenating the word index onto the representations for the rest of the words in the sentence actually works! Here is a very scientific drawing of this idea:

These models are also fast, because they can process multiple sentence indices at once (i.e batched).

In summary, models for Almost Semantic Role Labeling have the following benefits:

- Little added modelling complexity

- Ability to extract arbitrary numbers of events/relations/frames per sentence

- No slower in practice than NER, due to easy batching

Example 1: Bond Trading

(This is a real life example which I helped someone with a bit a year or so ago.)

Traders communicate with each other when buying and selling stocks on behalf of their clients. When they are doing this, they (apparently) use a very terse form of communication to describe what bonds they are talking about, at what date, at what price, and whether they are buying or selling. When they agree on a price, they manually copy and paste these values into a purchase order.

Being able to automatically extract and populate these orders is very valuable, because individual traders have individual relationships with other traders at different banks, and there is a bandwith limit - a single trader cannot talk to everyone at once. If these quantities could be automated, a buyer at any one time would have a substantially larger array of offers on the table at any given moment, because they could see offers from multiple other sellers that they did not personally know.

For example:

I'll bid [100 PRICE] for [20 QUANTITY] [BMW 4% 01/01/23 BOND]On the surface, this almost looks like NER, and for the single sentence case it basically is. However, it's possible to combine multiple calls into a single sentence, such as:

I can pay [100 PRICE], [200 PRICE], and [300 PRICE] for

[10M QUANTITY] [BMW 10s BOND], [20M QUANTITY] [BMW 4 01/20 BOND]

and [30M QUANTITY] [BMW'30s BOND]. where it becomes clear that really, these entities are actually associated with a particular bond, rather than being individual entities. In this case, an Almost Semantic Role Labeling model would work by viewing the price, quantity and dates as arguments to a particular bond. As the bonds have a very particular structure (market abbreviation, %, date), these can be extracted using a regex with high precision, similar to how verbs can be identified using a part of speech tagger in semantic role labeling.

Example 2: Slot Filling/Intent Recognition

Almost Semantic Role Labeling allows us to handle some of the more complicated cases in Slot Filling quite naturally. Typically, slot filling is framed as NER, because usually only one "event frame" is expressed per sentence. However, there are many quite natural cases where multiple events can be expressed within one sentence, such as:

Show me the flights between New York and Boston on the 3rd Aug and the trains from Boston to Miami on the 15th.Suddenly, just by adding a conjunction, this sentence is difficult to parse into events using NER, because we don't know which slots go with which events.

Show me the [flights TRANSPORT] [between V] [New York SOURCE] and [Boston DESTINATION] on the [3rd Aug DATE] and the trains from Boston to Miami on the 15th.

Show me the flights between New York and Boston on the 3rd Aug and the [trains TRANSPORT] [from V] [Boston SOURCE] to [Miami DESTINATION] on the [15th DATE].Your example here

Do you have another example of a task which fits this format? This blog is open source, and written entirely in Markdown files, so it's easy to contribute.

Semantic Role Labeling

Given i've been waxing lyrical about the benefits of viewing some structured prediction problems as almost semantic role labeling, let's take a look at what the real deal actually is. I'll also go about chopping up and re-organising the labels for SRL into something that I think could be generally useful as a "base" model for people to build applications on top of.

What is Semantic Role Labeling?

Semantic role labeling is one framework to describe "events" in natural language, which are normally focused around a verb (but sometimes also nouns) and it's arguments. These arguments also have thematic roles, such as "Agent" or "Instrument".

One commonly used dataset for semantic role labeling is Onotnotes 5, which is annotated using the Propbank schema. Propbank defines arguments for each individual verb, and a set of general purpose modifier labels which can describe alterations/additions to the main event, such as Purpose, Negation, Temporal and several more.

A common reduction of this task in the NLP community is to ignore that the argument definitions are specific to a given verb (i.e that ARG0 may have a different meaning for the verb "eat" than the verb "defibrillate"). In some sense this is a "poor man's" semantic role labeling, and at first glance it seems like such a crude hack would not work particularly well. However, in practice, the arguments for different verbs actually do tend to correlate; ARG0 typically represents the "Agent", or the person/thing doing something in the event, and ARG1 typically represents the "Experiencer". Because of these distributional similarities in predicate arguments in Propbank, this mangled version of SRL actually does carry some meaning, and as we are about to see, can be quite useful.

A Practical Analysis of a Bert-base SRL model

Let's take a closer look at a fine-tuned bert-base model for semantic role labeling on Ononotes 5.0, the most commonly used semantic role labeling corpus. This model is inspired by Peng Shi and Jimmy Lin's paper, but is actually even simpler (it uses only a linear classifier on top of BERT represenations, and uses a cute trick to repurpose BERT's sentence type ids as verb indicators). The implementation we are looking at is one that I wrote for AllenNLP and is the current model in the AllenNLP Demo. Here is the performance on the development set of Ontonotes 5:

Number of Sentences : 38377

Number of Propositions : 34783

Percentage of perfect props : 70.50

corr. excess missed prec. rec. F1

------------------------------------------------------------

Overall 70815 12454 11438 85.04 86.09 85.57

----------

ARG0 16355 1538 1281 91.40 92.74 92.07

ARG1 25176 3411 3053 88.07 89.18 88.62

ARG2 7919 1545 1611 83.67 83.10 83.38

ARG3 477 195 199 70.98 70.56 70.77

ARG4 470 138 113 77.30 80.62 78.93

ARG5 9 3 7 75.00 56.25 64.29

ARGA 0 0 4 0.00 0.00 0.00

ARGM-ADJ 169 105 85 61.68 66.54 64.02

ARGM-ADV 2051 1128 1117 64.52 64.74 64.63

ARGM-CAU 422 150 130 73.78 76.45 75.09

ARGM-COM 20 34 14 37.04 58.82 45.45

ARGM-DIR 341 185 208 64.83 62.11 63.44

ARGM-DIS 2527 539 473 82.42 84.23 83.32

ARGM-DSP 0 0 2 0.00 0.00 0.00

ARGM-EXT 143 108 130 56.97 52.38 54.58

ARGM-GOL 25 64 72 28.09 25.77 26.88

ARGM-LOC 1562 690 615 69.36 71.75 70.54

ARGM-LVB 48 12 7 80.00 87.27 83.48

ARGM-MNR 1399 601 594 69.95 70.20 70.07

ARGM-MOD 2778 71 46 97.51 98.37 97.94

ARGM-NEG 1508 80 53 94.96 96.60 95.78

ARGM-PNC 22 91 91 19.47 19.47 19.47

ARGM-PRD 104 328 312 24.07 25.00 24.53

ARGM-PRP 339 238 189 58.75 64.20 61.36

ARGM-REC 7 6 6 53.85 53.85 53.85

ARGM-TMP 5216 945 784 84.66 86.93 85.78

R-ARG0 919 69 83 93.02 91.72 92.36

R-ARG1 626 80 88 88.67 87.68 88.17

R-ARG2 40 18 17 68.97 70.18 69.57

R-ARG3 2 2 5 50.00 28.57 36.36

R-ARG4 1 2 1 33.33 50.00 40.00

R-ARGM-ADV 0 0 3 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-CAU 1 3 1 25.00 50.00 33.33

R-ARGM-DIR 0 2 1 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-EXT 0 0 2 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-LOC 74 39 15 65.49 83.15 73.27

R-ARGM-MNR 10 5 4 66.67 71.43 68.97

R-ARGM-MOD 0 3 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-PRP 0 0 1 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-TMP 55 26 21 67.90 72.37 70.06

------------------------------------------------------------

V 34783 1 0 100.00 100.00 100.00

------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------

corr. excess missed prec. rec. F1 lAcc

Unlabeled 74948 8321 7305 90.01 91.12 90.56 94.49

--------------------------------------------------------------------

One immediate take away from this table is this stat: Percentage of perfect props : 70.50. This means that 70% of the sentences parsed by the model have exactly correct argument and modifier spans for all verbs. Given how diverse Ontonotes is in terms of domains (it spans news, biblical text, conversations, magazine articles etc), this is really quite good! Additionally, the per-span and full sentence F1 scores are substantially closer together than for dependency parsing.

One reason for this is that SRL simply has fewer annotations, because it annotates spans and not individual words, so these scores are closer; this means there are less predictions to get correct in any given sentence. However, this doesn't completely explain the difference; syntax has many trivially predictable arcs and labels, such as punct and det. I suspect this difference is also infuenced by the granularity of the annotation, making it harder to annotate consistently (not to mention that the annotation requires experts).

The problems with Ontonotes 5.0 annotations

If we are taking a practical approach to semantic role labeling, there are several modifications we can make to the Propbank schema to improve performance and remove things we don't care about.

Discourse Arguments

In Ontonotes 5.0, one of the more common argument modifiers is Discourse.

Here are the annotation guidelines for the Discourse Argument Modifier:

!!! quote "1.4.12 Discourse (DIS)" These are markers which connect a sentence to a preceding sentence. Examples of discourse markers are: also, however, too, as well, but, and, as we’ve seen before, instead, on the other hand, for instance, etc. Additionally, vocatives wherein a name is spoken (e.g., ‘Alan, will you go to the store?’) and interjections (e.g., ‘Gosh, I can’t believe it’) are treated as discourse modifiers. Because discourse markers add little or no semantic value to the phrase, a good rule of thumb for deciding if an element is a discourse marker is to think of the sentence without the potential discourse marker. If the meaning of the utterance is unchanged, it is likely that the element can be tagged as discourse.

Note that conjunctions such as ‘but’, ‘or’, ‘and’ are only marked in the beginning of the sentence. Additionally, items that relate the instance undergoing annotation to a previous sentence such as ‘however,’ ‘on the other hand,’ ‘also,’ and ‘in addition,’ should be tagged as DIS. However, these elements can alternately be tagged as ADV when they relate arguments within the clause being annotated (e.g. ‘Mary reads novels in addition to writing poetry.’) as opposed to relating to or juxtaposing an element within the sentence to an element outside the sentence (e.g. ‘In addition, Mary reads novels’). Often, but not always, when these elements connect the annotation instance to a previous sentence, they occur at the beginning of the instance.

This raises several questions - why are we predicting something that doesn't change the semantics of the sentence at all, and secondly, how do we decide which verb in the sentence it should be a modifier for? Sometimes identifying the main event in a sentence is non-trivial. These discourse annotations are not consistently attached to, e.g the first or last verb in the sentence, and contain arbitrary annotation decisions which damage a model's ability to learn to predict them.

Argument Continuation

Ontonotes 5.0 annotates argument continuation, for cases where a predicate's argument is dis-continuous, such as:

[Linda, Doug ARG0] (who had been sleeping just moments earlier) and [Mary C-ARG0] [went V] to get a drink.

["What you fail to understand" ARG1], [said V] [John ARG0], ["is that it is not possible" C-ARG1].

This annotation is implemented in a very "hacky" way in Onotonotes - the label is just prepended with a C- to mark it as being continued, and people typically just add it as another label in their model. This is quite gross, both from an annotation and a modelling point of view - but at least the evaluation script merges continued arguments before scoring, so they are at least correctly evaluated.

For the core arguments, this type of continuation is not too uncommon, but are vanishingly rare for argument modifiers. Here are the span counts in the training and development splits of Ontonotes 5.0:

Arg Train Dev

# Core Arguments

C-ARG0 182 33

C-ARG1 2230 329

C-ARG2 183 24

C-ARG3 9 1

C-ARG4 16 1

C-ARG5 0 0

C-ARGA 0 0

# Modifiers

C-ARGM-MNR 24 8

C-ARGM-ADV 17 2

C-ARGM-EXT 14 1

C-ARGM-TMP 12 1

C-ARGM-LOC 9 0

C-ARGM-DSP 2 0

C-ARGM-CAU 2 0

C-ARGM-PRP 1 0

C-ARGM-MOD 1 0

C-ARGM-ADJ 1 0

C-ARGM-DIS 1 0

C-ARGM-NEG 1 0

C-ARGM-COM 1 0

C-ARGM-DIR 1 0Taking a look at some of the occurences of modifier continuation in Ontonotes, it is either incorrect annotations, or very complex conditional statements within the modifier, such as "X happened either before Y, or after thing Z, but not both". In this case it seems to make sense to me to annotate these as separate modifiers - you could detect the presence of ambiguity for a given modifier just by seeing if a particular verb has multiple modifiers of the same type or not.

Argument Reference

The second complexity for argument span annotation in Ontonotes is argument reference. Argument reference occurs when arguments to a verb are referenced (duh), such as:

[The keys ARG1], [which R-ARG1] were [needed V] [to access the car ARGM-PURPOSE], were locked inside the house.

This reference commonly occurs in cases where you would use words such as "that", "who", "they", "which" to refer to an object or person (relative pronouns). A slightly more complicated type of reference which is a bit more interesting occurs when there is a forward reference to an argument which occurs later on, such as:

[Anticipated for 20 years R-ARG1], [today ARGM-TEMPORAL], [this dream ARG1] is [coming V] [true ARG2].

However, this type of reference is quite rare, compared to the relative pronoun case which happens very frequently. We can see this by looking at how often the different Ontonotes labels are referred to, below:

Arg Train Dev

R-ARG0 7307 1002

R-ARG1 5489 715

R-ARG2 400 57

R-ARG3 44 7

R-ARG4 10 2

R-ARG5 1 0

R-ARGM-TMP 494 76

R-ARGM-LOC 682 89

R-ARGM-CAU 39 2

R-ARGM-DIR 11 1

R-ARGM-ADV 14 3

R-ARGM-MNR 75 14

R-ARGM-PRD 1 0

R-ARGM-COM 3 0

R-ARGM-PRP 5 1

R-ARGM-GOL 4 0

R-ARGM-EXT 5 2

R-ARGM-MOD 1 0

Again, we see that there is a long tail of argument reference, roughly corresponding to whether the argument is typically used to refer to something concrete. In particular, it's vanishingly rare that these argument reference anotations add a huge amount to the understanding of a particular verb's arguments, because in every case that an argument's reference is annotated, the argument is also annotated.

Purpose, Cause and Purpose Not Cause Argument Modifiers

The final discrepancy I picked up on when looking at a confusion matrix of the BERT-based SRL model's output is that Ontonotes 5.0 contains Purpose, Cause and Purpose Not Cause labels. This is likely a hangover from different versions of the Propbank schema being used to annotate different versions of Ontonotes, because this (original?) version of the schema contains only Cause (CAU) and Purpose Not Cause (PNC) argument modifiers, but version 3.0 from 2010 contains only Cause (CAU) and Purpose (PRP) modifiers. However, the fact that all 3 are present is problematic, because it will cause any model to be unsure of whether to assign PNC or PRP as a label. Not to mention the frequent ambiguity purpose and cause in the first place - the line of causation in event semantics is quite blury.

In order to temporarily fix this problem, I took the relatively nuclear approach of fusing all of these argument modifiers in to a single one. ducks for cover

Simple SRL

I don't have the details of this completely finalised yet, but here is an SRL model with the following alterations to the label space, taking into consideration the above points:

- Drop the Direct Speech Argument Modifer (2 examples in entire of Ontonotes)

- Drop the Reciprocal Argument Modifier (very uncommon, use unclear)

- Drop the Discourse Argument Modifier (Common, but not useful, arbitrarily annotated)

- Drop all Argument Modifier continuations

- Only allow Argument/Modifier reference for the core arguments and the CAUSE, LOCATION, MANNER, and TEMPORAL modifiers (this was a bit arbitrary, but it was based on arguments that are typically referenced based on the label distribution.)

- Merge the PURPOSE, CAUSE, GOAL and PURPOSE NOT CAUSE into a single CAUSE label (if I did this again, I would merge the GOAL label with the DIRECTION label, beause they are more similar.)

Modifying the label space in this way, we get results that look like this:

Number of Sentences : 36041

Number of Propositions : 32449

Percentage of perfect props : 73.67

corr. excess missed prec. rec. F1

------------------------------------------------------------

Overall 62450 9728 8913 86.52 87.51 87.01

----------

ARG0 15206 1222 1034 92.56 93.63 93.09

ARG1 23644 2763 2412 89.54 90.74 90.14

ARG2 7515 1278 1328 85.47 84.98 85.22

ARG3 473 169 158 73.68 74.96 74.31

ARG4 445 111 105 80.04 80.91 80.47

ARG5 9 3 7 75.00 56.25 64.29

ARGM-ADJ 164 100 90 62.12 64.57 63.32

ARGM-ADV 1978 1033 1035 65.69 65.65 65.67

ARGM-CAU 897 370 318 70.80 73.83 72.28

ARGM-COM 18 25 13 41.86 58.06 48.65

ARGM-DIR 335 168 180 66.60 65.05 65.82

ARGM-EXT 151 112 112 57.41 57.41 57.41

ARGM-LOC 1361 536 544 71.74 71.44 71.59

ARGM-LVB 47 10 7 82.46 87.04 84.68

ARGM-MNR 1332 493 513 72.99 72.20 72.59

ARGM-MOD 2547 51 50 98.04 98.07 98.06

ARGM-NEG 1406 71 49 95.19 96.63 95.91

ARGM-PRD 90 213 299 29.70 23.14 26.01

ARGM-TMP 4832 825 659 85.42 88.00 86.69

R-ARG0 0 48 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARG1 0 74 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARG2 0 4 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARG3 0 1 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-CAU 0 3 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-LOC 0 27 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-MNR 0 1 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

R-ARGM-TMP 0 17 0 0.00 0.00 0.00

------------------------------------------------------------

V 32448 0 1 100.00 100.00 100.00

------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------

corr. excess missed prec. rec. F1 lAcc

Unlabeled 65435 6743 5928 90.66 91.69 91.17 95.44

--------------------------------------------------------------------and volia! Our overall performance has improved (unsurprisingly). But there are several interesting things to note here, the first being that as our F1 score has increased by 2.44, the percentage of perfect props has increased by 3.17%, suggesting that many of our corrections have contributed to fixing the last incorrectly predicted span in a particular sentence in the dev set. This is quite encouraging! Another thing to note is the unlabeled span F1 has increased by 1%, indicating that the spans we completely removed were also hard to predict - it wasn't just identifying the labels for those spans that was difficult.

Finally, to place this improvement in the context of modelling, a 3% performance increase is similar to the modelling contributions between 2008 and 2017 (admittedly this is measuring on CONLL 2005, a different SRL dataset), and slightly more than the increase given from incorporating BERT representations into the SRL model. Quite nice! The takeaway here is to look at the data and to make sure you're actually interested in what you are modelling.

Annotation benefits of SRL

One additional benefit of SRL and SRL - adjacent formalisms is the research coming from the University of Washington/Bar-Illan University on how to annotate this data efficiently. The overall idea is to use natural language questions (mostly from templates) to extract argument spans for particular roles. This abstracts away the linguistic knowledge required to annotate this data, but also, from a more practical point of view, makes it easy to modify the label space of annotations by changing the question templates. The QA-SRL project has a website with a nice browser to look at the freely available data.

- Question-Answer Driven Semantic Role Labeling: Using Natural Language to Annotate Natural Language

- Large Scale QA SRL Parsing

- Crowdsourcing Question-Answer Meaning Representations

One under explored aspect of QA-SRL in my opinion is the natural way it can be used to collect annotations in an online fashion, in an actual application. For example, the schema for questions in the trading example above could be something as simple as:

- What is the price of this bond?

- What quantity of the bond is requested?

- Is this bond being offered or sold?

This might seem obvious (converting the labels to questions), but really the step forward here is recognising that creating annotations to train an effective NLP model for predicting this content requires you to view it as Almost Semantic Role Labeling and not NER.

Conclusion

Overall, I hope this post spelled out a couple of ways that we might be underestimating the performance of semantic role labeling models because of linguistically fiddly details that we can ignore in practice, as well as some labels which don't really make sense. In the NLP research community currently, there is a huge focus on the models we train on these large, carefully annotated datasets, and not a huge amount of introspection on the datasets themselves, particularly in terms of correcting or modifying label schemas or annotation frameworks.

If you have feedback, let me know on Twitter!